FIGMENTS

&

PIGMENTS

Studio session with abstract artist Callum Schuster

on the psychology of colour, memory, and magnets

Photography by Aakanksha Luthra + Callum Schuster

NEWEST:

Is your studio an insight into your brain or heart?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

Maybe both? Could be one in the same but perceived separately, with the object as the brain and the colour as my heart. The physical studio is just the body that contains all of these disparate objects and memories. Bridging between the imaginary, the body, and environment and how these separate things imprint themselves on the mind and how this is further expressed and put back into the world is how my brain processes my work. A kind of cyclical nature via nurture and vice versa.

That shelf has a lot of things I’ve collected over the past few years.

There’s oxidized bullets, a moose antler and tooth, a rock from India, my childhood teeth, lapis lazuli from northern Chile that a friend gave me.

Little memories of events and places that I’ve been to. Assembling this archive instead of journaling or writing a diary, has been my way of marking moments in my life. I’ve been thinking about all the different things that have happened here, over the last 10 years. It feels lucky to have a space that can provide for so many different activities, and can be shared with so many different people. I’ve been in this unit for six years, and experienced some major landmarks in my art career here.

NEWEST:

Can you tell me about these pigments that you’ve made?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

It’s been around eight years of collecting—mostly rocks, but also plants and some other bits, like metals, plastics, different food products like spices and dried soups, and other sorts of strange things from abandoned places. Most of what I’ve collected is labeled, but if they’re not, I can usually identify them just based on the colour.

NEWEST:

How do you extract this and what do you decide on bringing back?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

It starts with a moment, a recognition of something special. When that happens I’ll scan the surrounding area for a rock or something to remember it, maybe one with a particular colour.

I then grind it into powder to extract the colour and use it as a kind of swatch to symbolize the memory.

NEWEST:

Do you feel bad destroying it?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

It was a challenge at first.

The first time I had this relationship with colour I was in my early teens, and I picked up a shell with a purple vein that I collected as a boy in Scotland. The colour is what triggered the memory of collecting it, not the shell itself.

To hold on to that memory more efficiently, I felt like I had to crush the shell and get that purple, and set it aside as its own. It was a huge challenge, because I didn’t know what I was doing. I could have totally screwed it up. A lot of these pigments aren’t lightfast, so they fade regardless, but it’s an interesting dilemma. I heard a proverb on memories recently that it’s like holding sand—you can only hold on to so much, you’re inevitably going to lose some through the cracks of your fingers. I relate to colour like a spectrometer, refracting the different tones based on the various chemical or elemental components present. This technique has been really pivotal for me, as a method of wayfinding through my past. Each colour gathered acts as an index or signature for an event or moment.

NEWEST:

It’s interesting how you compare colour to memories since the latter can fade with time or be misinterpreted. How does that factor into your philosophy?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

Memory is an interesting thing because it can be scaled.

I do believe in the collective unconscious to a degree, and more so in the somatic archive, something primordial and deeper within all of us.

Our communal relationship to colour is something that can bring people together. Red has a similar effect for a lot of people, and iron red has an intense symbolism to it. As one of the elements created in the Big Bang, it became one of the main components of our sun, the giver of life. Red is in our blood, we immediately know its danger, and you can enter the concept/feeling/experience of red from many different doors, but ultimately, this relationship came from what we might consider the beginning of perceived existence.

NEWEST:

Do you feel that some of this work stores energy and even power that can be healing or traumatic?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

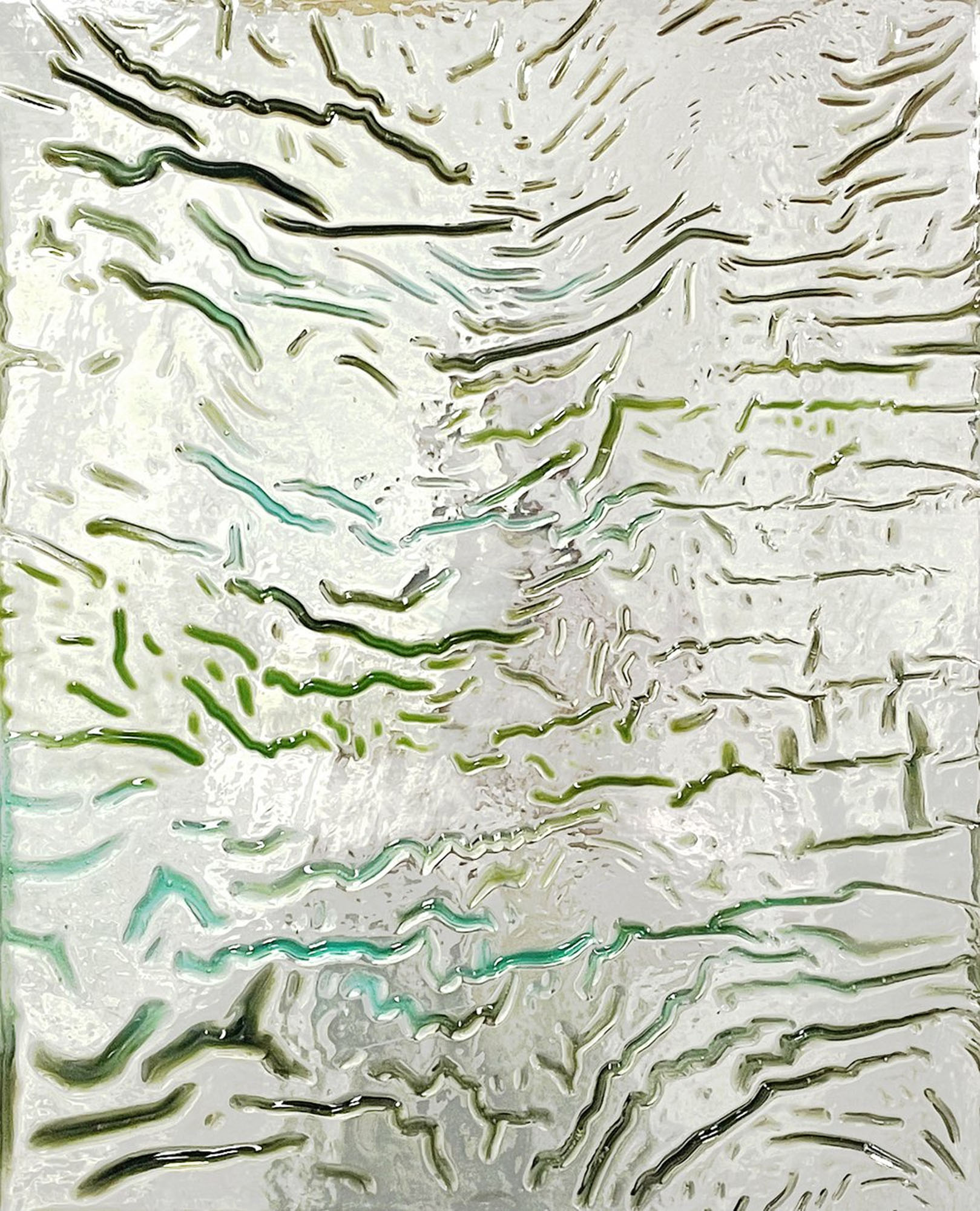

Light is a phenomena of nature and colour is a phenomena of the mind. Integrating magnetic fields into the colour fields was a way of relating mind and body or mind and nature.

This work is simple in that it’s like pointing a finger at something and giving it a name based on your relationship to it. The colour is taken from a specific moment in time and space.

This orange piece, for example, is a brick; that’s what it was made from, but the magnetic pattern that I created within it, is my idea of it. The relationship between the thing itself and it’s memory doesn’t always correspond to expectations.

NEWEST:

How do you create the colours from the objects you select?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

Mortar and pestles. I grind it down into a fine dust or I soak it in a solvent like ethanol, oil, glycerin or water with different PH.

NEWEST:

Do you usually know what colour you’re going to be getting out of an object?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

In the beginning, no, but at this point I have a pretty good idea. Sometimes it works out really well, but then I’ll come back to the studio the next day and the colour’s completely faded, turned to yellow or white or clear. It can be a very short lived experience.

NEWEST:

I know it’s like asking which child you prefer, but which pigment is your favourite?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

This is the first pigment I ever made—it’s a copy of an Egyptian blue. It’s oxidized copper, created in a certain way to try to mimic that ancient recipe.

George Washington Carver is a personal hero; he’s usually remembered for agriculture but he could also be considered one of the first abstract artists.

Using soil samples from and across the US he created some of the first painted monochromes. He also oxidized copper to recreate the Egyptian blue and was one of the first to get it right. This sumac red is personal to me because it’s from High Park and I was born across the street from there. It feels like more than one colour to my eye. There’s two sets of pigments in this box, which were a gift. The bottom row is from one of the world’s last pigment grinding windmills just outside Amsterdam. The top row is from an area called the Sacred Valley in Peru. My brother lived close to there and brought them back.

NEWEST:

That’s incredible. So he brought back objects that you have or he brought back the pigments themselves from a market there?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

Somebody was making the pigments in the market for others to dye their wool or other textiles. I think that’s how I first came to the connection of memory and colour.

The ability to hold memory is colour’s greatest asset for me. It became inevitable as I started collecting colours.

Some of these colours come from construction sites around Toronto. This city is changing so quickly, and as my home I’m trying to document these changes. When they’re demolishing sites like my aunt and uncle’s house or Honest Ed’s, I’ll try to get there quickly to retrieve some kind of souvenir. Once they’re gone, the stories don’t mean as much. In a time when everything’s go, go, go we’ll forget to stop and remember those things, so the ephemera helps. This was something I learned in a book my other brother gave me called Wisdom Sits in Places.

NEWEST:

What’s the motivator for you?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

A lot of these bigger pieces on the wall were from my last show, which was about the idea of home, whether it’s a place within you or a place outside of you, that you seek. I moved into an apartment built on top of the site of my childhood home. My current bedroom window is approx. 200 feet away from my first childhood one.

When I moved in, the smells from High Park and other sounds were unlocking dreams I had as a kid; it felt like a ‘to be continued’ episode. I had these great memories and a really powerful feeling of home, but also woke up feeling disassociated, with this distortion of time, because the physical “home” wasn’t there.

There are certain landmarks that help ground me, but as these landmarks change I have to find peace within myself first, before moving forward.

I didn’t know what I was doing at the beginning when I was breaking apart and reconstituting my childhood shells and stones. I wasn’t sure where it would lead but it’s been a really interesting way of marking the moments in my life.

NEWEST:

I sometimes wonder why we hold on to memories, these cherished moments so much. Why is that important to us? Why is it so important to you?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

There’s this story by Plato called Phaedrus. I haven’t read the whole thing, but I found certain parts to be really illuminating. In the beginning Socrates asks Phaedrus, “Where did you come from, and where are you going?” His response is basically, “I came from over there and I want to go over here” so they decide to go for a walk and figure it out. Probably not the best summary, but what I took away from it is:

you are the fulcrum between your past, and your future; your memories and your goals create who you are now. As you move forward in time, you’re always caught in between your past and your future, and where you came from will inform where you want to go.

Where you want to go will be determined by where you came from, so it’s all very cyclical.

NEWEST:

I hate the word authenticity, unless it’s pertaining to an object. I think genuine is more appropriate, that you’re as honest to yourself as you can be, within the parameters you’re dealing with at any given moment.

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

I think things in life are allowed to be incomplete.

You can imagine a perfect circle, but that’s not the world we live in. It, and we, are in a constant state of flux. We have to find peace with the limits of existence, while our imaginations go far beyond reality.

NEWEST:

How has your practice changed over the past year and how has being in nature influenced it?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

Those changes happened kind of simultaneously, I was very lucky to be able to have that kind of space to explore.

Some of my happiest memories at an early age were being in nature, the way it made me slow down.

I feel more integrated into the way the seasons change, especially in Canada. Being in one place, with so many plants throughout one year, learning the little dances between each season, and finding my place amongst that was very rewarding and beneficial.

I found it more difficult coming back to the city, with the different pace of city life, but I like observing that. Trying to maintain momentum, and find ways to adapt. That slower pace has also changed how I collect memories, it’s way more deliberate.

I’ve noticed that the only two paintings I made last year were for my mother and father. They were similar to my pieces with magnetic iron dust and natural pigments, but there were more layers. I found that I was able to tell a more intimate story through those layers of colours and abstract images than before.

NEWEST:

Were they able to understand the context, the complexities of what you’re trying to share?

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

Yes, at least most of it. The piece I made for my mother’s birthday had five pigments; five layers with five different magnetic fields, all taken from our 2014 Istanbul trip. That was really magical. I also made the imagery a bit more symbolic because of what I was taught and what I observed about Muslim culture which she could see too. For my father, I made a similar sized painting, but it was a diptych. I referenced a photograph from a bike trip we did together in Spain. Taking the residue of the rocks, flowers and other bits I’d collected, I was able to recreate the photo in a basic, Etch-a-Sketch way, pulling the iron dust into the same pattern as the two bikes in the landscape. As the iron dust was exposed to the magnets, the colour fields amassed together, creating an abstract photo of the literal one, as all the original pieces were from that specific place. He felt that as well.

I always thought I was a better communicator visually, but that was a kind of ‘aha!’ moment where I was able to hand someone an image, and they understood it immediately. Usually, it’s something only I feel that other people experience vicariously, so to have someone else share the original moment was pretty cool.

I’ve also had close friends provide me with meaningful objects from their travels, which I recreate into a sculpture through which the memory can be shared.

NEWEST:

You’ve mentioned the importance of your grandmother before…

CALLUM SCHUSTER:

It’s been a year since she passed away. She was my best friend, we were together almost every Sunday for dinner. We weren’t able to see her much during the first lockdown, but we adjusted things so we could see her more and then she passed away with family, so there’s closure.

One of the last lessons she told me was how weIcome out of the pandemic will be really important, and not to forget our grace and compassion.

That experience has me thinking a lot about where we come from, and where we’re going, and the answer is forward. Despite looking back and holding on to our memories, which made us who we are, there has to be some sort of future. Right now, I feel like I’m in a state of transition, which is a bit intimidating. I’ve been slow to peel the bandaid off, so I’m trying to move forward with clarity, and less resistance. Resistance to the fear of what might happen.

I find solace in the expression, how do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time, you cannot eat it all at once.